‘The people’s judge’ finds his roots in Memorial Union

By Kayla Schmidt x’15

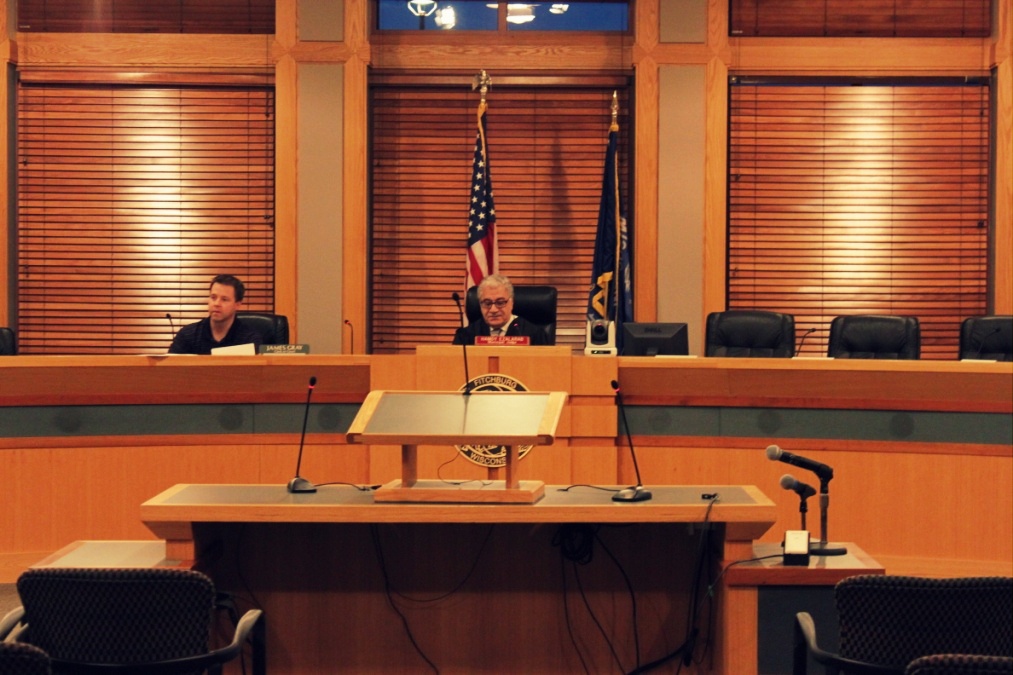

Judge Ezalarab waits for his next trial at Fitchburg Municipal Court.

On a bitterly cold February night, Judge Hamdy Ezalarab looks over his bench across the small, carpeted courtroom to address his next case. Bright overhead lights glare against the shuttered windows that block breathtaking winds; a young man at the podium requests two weeks to pay his fines for a traffic violation. Judge Ezalarab gives him 60 days.

Forty-five years ago, Judge Ezalarab looked over a different type of bench. Instead of young men and women asking him to reduce license point deductions or extend fine deadlines, they ordered burgers and beer at Memorial Union’s Der Rathskeller where he worked as a student employee.

Born in Egypt during what he describes as “the great days of Cairo,” Judge Ezalarab came to the United States in his early twenties where he eventually earned a PhD, three master’s degrees, a law degree and a bachelor’s degree in agricultural economics.

Judge Ezalarab began his Union career as a dishwasher, then became a bartender in Der Stiftskeller and was eventually promoted to supervisor, but he did various other jobs along the way. Serving ice cream, performing financial duties or working with bands, “I did everything,” Judge Ezalarab explains. “While working in the kitchen I once had to carry heavy trays and ended up spilling dishes everywhere.”

Judge Ezalarab and his wife, Susan. The two met in 1969 while they both worked in Memorial Union.

But Der Rathskeller wasn’t just Judge Ezalarab’s work place; it was also his podium. In the late sixties, the Vietnam War and civil rights were commonplace topics on campus. Students, faculty, staff and community members gathered to debate and discuss these controversial issues, particularly in Memorial Union, truly making it “the living room of campus.”

Described by his friends as the “Lionel Richie look-alike,” Judge Ezalarab became a well-known face in Memorial Union through his activism and involvement in public affairs. His devotion to helping others inspired him to take an active role in establishing the first organized student employee labor union. From 1971 to 2004, the Memorial Union Labor Organization negotiated collective bargaining agreements that addressed basic worker protections such as hours of work or seniority. “We were too busy feeling for the poor and oppressed that you didn’t worry about yourself. No one went to football games at the time. We had a war going on.”

After a while the role of “counselor” informally became part of Judge Ezalarab’s duties. When the Mendota Mental Health Institute went through the process of deinstitutionalizing patients, many of them started hanging out in Der Rathskeller. Judge Ezalarab got to know several of the patients and they came to rely on him for guidance.

“They would tell me their problems so I would try to give them help,” Judge Ezalarab explained. Many were simple conversations across the bar, a tip of advice given or a reminder to take their medication. One odd situation still sticks out in Judge Ezalarab’s mind. “I once had to stop a woman from performing a strip-tease in the middle of the room!”

After four years, he left the Memorial Union and Der Rathskeller’s electric atmosphere to find other work. But to Union-goers he continued to be Der Rathskeller’s “go-to-guy.”

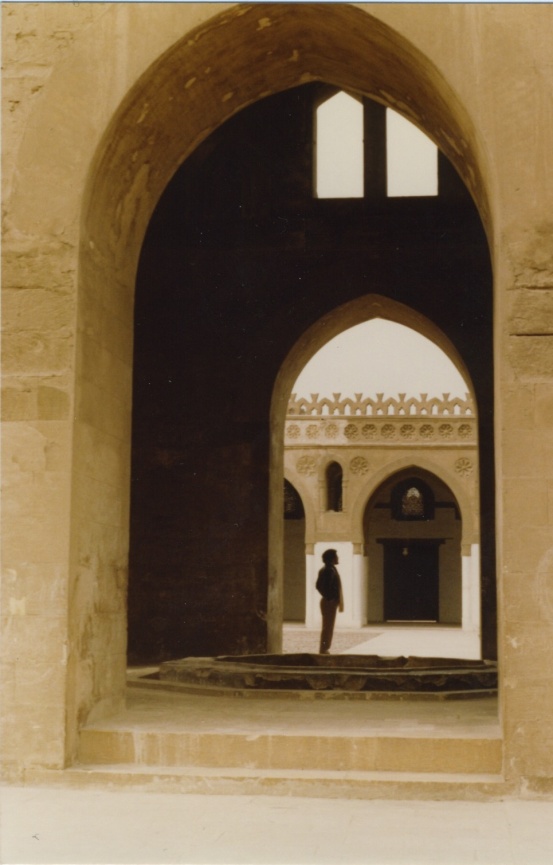

Judge Ezalarab during a visit to Egypt, where he was born.

“After I got a different job as a state senior research analyst, I would come back to the Union and people still thought I worked there,” Judge Ezalarab said. “One man approached me and started talking about how he lost his quarter in the jukebox. They almost expected me to be there forever.”

It wasn’t just all politics and work for Judge Ezalarab. In 1969, he met a young woman named Susan who happened to also work in Memorial Union. Susan worked in the cafeteria and eventually became his wife.

Judge Ezalarab’s passion for helping people remains as strong as ever. He currently serves as the first publicly elected Muslim municipal court judge for the City of Fitchburg. He is also Chief Administrative Law Judge of the Madison Division of Worker’s Compensation, where he supervises 15 judges, and is one of five expulsion judges for Madison Metropolitan School District . “Each court has its own legal procedures. One day I’m going to get everything scrambled,” Judge Ezalarab laughed.

Judge Ezalarab loves to participate in what he describes as “the people’s court.” “Fitchburg court is my joy,” he said.

Following in the footsteps of his “disciplined but generous” father, the judge is serious during court, but a gentle smile slips through from time to time.

“I always go home and worry about how my decisions may have affected someone,” Judge Ezalarab explained. “When I take away a driver’s license I wonder ‘what if they were the only person in their family with a car, or how are they going to bring home their groceries?’ I worry most about our kids’ future. That’s why Fitchburg has the first juvenile diversion program where we divert kids from the criminal justice.”

Judge Ezalarab is referring to the Phoenix alternative program, which allows teens in the Madison Metropolitan School District facing expulsion to follow an alternative program and avoid an expulsion hearing. “It is a beautiful program and I definitely utilize it,” he said.

Judge Ezalarab loves his work and can’t imagine retiring. But he also looks forward to a day where he can travel and speak freely about religious and political issues without the constraints of his position as a judge. He explained that although he was born Muslim, religion has never been a huge influence for him.

“My wife is Catholic. I am Muslim. We have not argued once about religion,” Judge Ezalarab said. “I am not saddened if a Muslim becomes Christian or Jewish. I’m extremely comfortable in dealing with my friends who are atheists who were once Muslim. Human values are the essence of our morals and faith. Faith comes from the heart and if it’s good, it will survive. Until more people believe this way, there will still be war.”

Judge Ezalarab slips a smile during a Fitchburg Municipal Court hearing.

War remains in the headlines today as in 1969. Still, Judge Ezalarab continues to fight the little battles, whether it’s getting a drunk driver off the road or helping a teen through a difficult time.

And yet with all the jobs on his plate, Judge Ezalarab still wishes for time to take part in new experiences, one of which includes traveling the world with his wife, Susan. “I want to take her on a long trip. I want us to eat good food in China or maybe India,” he said.

“I have a long list of things I still want to do.”