Preserving Paul Bunyan: saving one of the Union’s most treasured rooms

By Herschel Kissinger & Zach Thomae, Wisconsin Union interns

Being in the Paul Bunyan Room earlier this June was like watching a story being untold. At first, the room was alive with warmth and color with the tales of Paul Bunyan being illustrated on all four walls. As the hours grew longer, the story came down in pieces, unscrewed and dismantled panel by panel, until all that was left were empty walls.

A woman named Joan Gorman oversaw the process, guiding Union facilities workers as they took down the panels, unscrewing bolts and wedging the boards of the walls. She wrapped the pieces—some of them easily twice her height—in a plastic film at a table, preparing them to be packed away in foam-lined crates.

Joan Gorman and Wisconsin Union employees Joe Padgham and Ron Watts carefully work to take down the panels

One would expect a kind of depressing atmosphere to flood the room as those historical paintings were taken down. But any melancholy overtones were washed away by conversation and even laughter. Joan wasn’t fazed by the blank walls. To her, uninstalling these murals was not like preparing the dead for burial or bidding farewell to a longtime companion. It was more like just packing for a trip– very carefully packing for a trip.

Joan serves as senior paintings conservator at the Midwest Art Conservation Center, a regional non-profit organization “providing treatment, education, and training” in art conservation and preservation. The organization has an extensive history with the UW-Madison, including preserving the John Steuart Curry murals while the biochemistry building was being rebuilt. The Paul Bunyan Room conservation is their first project with the Wisconsin Union.

The murals have been a part of the Memorial Union for more than seventy years. But now that the Paul Bunyan Room is closing for the first phase of the Memorial Union Reinvestment, the murals need to be moved to a temporary new location for safe-keeping and protection from construction vibrations.

Legendary history

The Paul Bunyan Room was part of the original construction of Memorial Union at the encouragement of tall-tale enthusiasts, including many at the Wisconsin Historical Society.

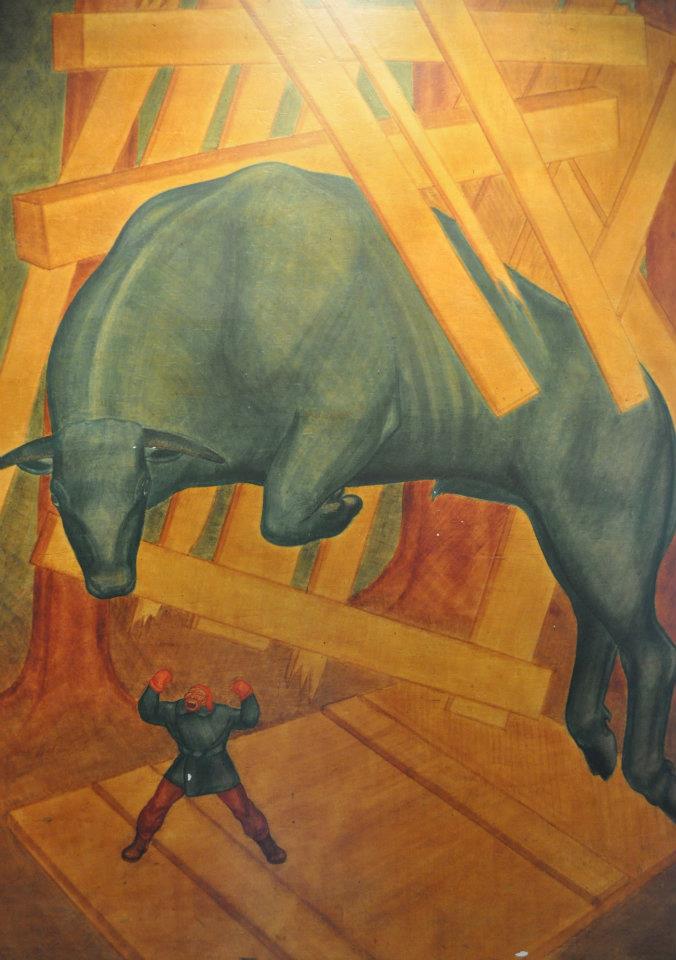

It was the late 1920s, and Paul Bunyan and Babe the Blue Ox tales were at the peak of their popularity. Stories of a hard-working giant cutting down a grove of trees in one swing, or eating from a griddle greased by men skating on bacon slabs flooded American folklore. By the time artist James Watrous pitched his mural idea, the Paul Bunyan tales were embedded into our cultural heritage.

In 1933, the Public Works of Art Project, a New Deal program, had started funding the creation of artistic works for public buildings. James Watrous proposed an idea for a set of murals based on the Paul Bunyan legends to fill the walls of his namesake room, and was hired to paint the murals that December.

The murals have been a Memorial Union mainstay ever since. And not just as background art meant to fill the space of an existing room–by all means, the murals are worthwhile as works of art themselves. “They are a jewel in a building that’s a jewel to the University,” Joan says of the room.

To Joan, the fact that Watrous painted more than 40 cohesive pieces is a testament to his dedication and patience toward the project. “The designs of the murals are fabulous, full of life and movement and bigness. It’s all about bigness.” And although the program was only funded for six months, Watrous used his free time to continue it to completion in 1936.

Further demonstrating Watrous’s dedication as an artist is his chosen medium: egg tempera. In this process, powdered pigments are added to a mixture of water and egg yolk. Choosing to paint in egg tempera was like choosing to hand-stitch a wedding dress when a sewing machine was readily available. Tempera (a style hardly used in recent centuries) is much slower and easier to mess up than other styles like oil painting. To plan the compositions of all the panels and then to execute them at a snail’s pace is a remarkable feat, to say the least.

Preparing for slumber

The “bigness” of the murals made it a challenge to remove them for storage, but Joan and a number of Wisconsin Union employees were successful. And even after being up for over seventy years, the pieces are in remarkably good condition: except for one panel that sustained a small amount of water damage, they are only marred by the usual suspects in a room meant for socializing – food grease, humidity from open windows, cigarette smoke, and a few marks from bumps and scratches.

Joan’s takes a minimalist and transparent approach to her conservation work. “Our principles are ‘do no harm’ and ‘less is more.’ Anything we add to an object should be detectible by another conservator, should be reversible without harming the object, and should be durable. And the chemicals shouldn’t change over time.”

Joan’s takes a minimalist and transparent approach to her conservation work. “Our principles are ‘do no harm’ and ‘less is more.’ Anything we add to an object should be detectible by another conservator, should be reversible without harming the object, and should be durable. And the chemicals shouldn’t change over time.”

However, with the good condition of the Paul Bunyan Room murals, Joan doesn’t expect very much will have to be done to them at all. She recounted one tale of a different project where a single mural was cut into 60 pieces and needed to be stitched back together. Compared to that, the Paul Bunyan project is easy–just like packing for a trip.

Right now the project is in the waiting period between two major steps: dismantling and re-installation. When it comes time to return the panels to their rightful places in the restored room, art conservators will likely need to create a new hanging system that makes the panels easier to remove for future cleaning or restoration.

For now, the Paul Bunyan Room is closed. The walls are empty, and the murals have been moved out. And we are counting down the days when the beautiful giants are returned to their rightful places in one of the most historic and beloved spaces in the Memorial Union.

For now, the Paul Bunyan Room is closed. The walls are empty, and the murals have been moved out. And we are counting down the days when the beautiful giants are returned to their rightful places in one of the most historic and beloved spaces in the Memorial Union.